Valpane

since 1898

in the heart of

Monferrato,

Piedmont

In just over a century,

three people

have made the history of Valpane

Pietro Giuseppe Arditi

known as "Giuspin"

Early 1900s: in Cellamonte, an elegant town on the Monferrato hills,

Pietro Giuseppe Arditi (known as Giuspin) lived with his family, comprised of a brother and four sisters, each of whom was in search of their own path in life.

Pietro, for example, was very attracted to the world of wine, to the point of starting to rent some vines on the surrounding hills: the grapes produced were good, and he knew how to make a special wine.

However, there was an estate near his home, called Valpane, that had always fascinated him: well exposed, it dominated the valley with the size of the large villa and a slender tower with a clock, the chimes of which marked the time for all those (and at the time they were many) who did not own a personal watch. The slopes well exposed to the sun and the calcareous clay soil were ideal for producing excellent grapes; in fact, the Valpane wines were exported to Belgium and Switzerland and in 1898 they won the gold medal at the international exhibition of Dijon and Bordeaux and the silver one in Hamburg and Rome.

Unfortunately, in recent times the Valpane estate seemed neglected, because its owners, the Fojadelli’s, could no longer take care of it as they once did, having reached a certain age. It was then that Pietro Giuspin Arditi decided to ask to rent some of those lands.

He left his house in Cellamonte dressed in his best suit, and we can imagine him walking through the valley, repeating to himself the words with which he would present his request.

The elderly owner received him, he listened for a while to his proposal and his plans, but in the end, he abruptly rejected: the Fojadelli’s were not interested in renting their land, not to him nor anyone else.

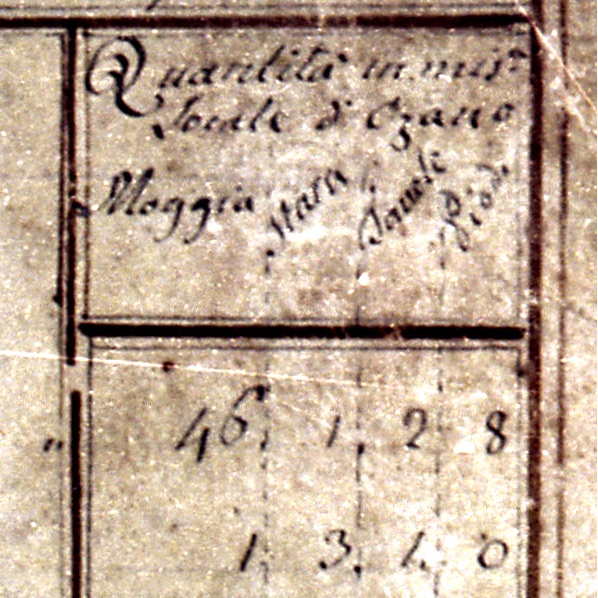

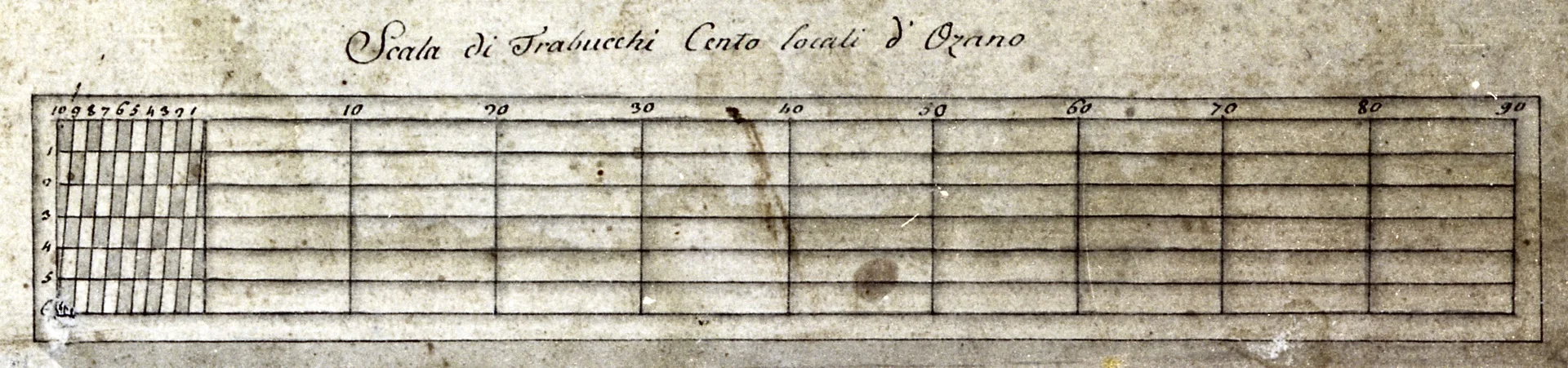

A contract redacted at Valpane in 1900

Pietro saw all his plans and dreams collapse in an instant: he took leave from Fojadelli and as soon as he got to the courtyard of the villa, he burst into tears. He thought he was alone, but an old maid of the Fojadelli house saw him crying from a window on the first floor. Imagining that something had gone wrong, she ran to her master, with whom she had a certain trust, and asked him what had happened: why had he sent away so badly that young man, known to all as a great chap, a great worker and a good person? Did he know that everyone in the village respected him for how he managed the vineyards he rented and the wines he produced?

Old Fojadelli was struck by what the woman was telling him, and in the end asked the maid to run after Pietro and to invite him to come back: he would lease him the vineyards he had asked for.

It was the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the Valpane estate.

”Pills from my kitchen and wine from my cellar”

Pietro and Teresa Arditi

Having worked hard, in 1902 Pietro managed to buy the estate; he planted new vineyards and renewed the older ones, while continuing to produce excellent wine. He never drew back when faced with struggle, but he also knew how to enjoy life; in fact, he married Teresa, a beautiful tall, thin girl, 15 years younger than him, and almost every evening he would go to Cellamonte, by foot or by carriage, to play cards with friends. He was even famous for his skill in dancing the waltz. He was strict with those who worked for him, but also very generous. During the terrible crisis of 1929, a great number of people went to look for work from him, so as not to suffer hunger, and Pietro did not send anyone away; since then, his fellow villagers cherished him even more. At 88 he still went to work in his vineyards and to those who asked him what medicine allowed him to be so active and bright, he replied: "Pills from my kitchen and wine from my cellar".

He died at 92 years of age, in a very snowy February; the whole town attended his funeral. Despite the frost and the snow, in fact, the church and the square in front of it were packed with people, because everyone wanted to pay the last farewell to who had been able to do so much good for others.

Lydia Arditi

Lydia was the eldest daughter of Pietro Giuseppe: like her brother and sister, as a child she was sent to study at boarding school, where she proved to be a very bright student, especially in mathematics. For this reason, her teacher was very upset and tried to oppose her parent’s decision to end her studies: it was a pity that such a talent go to waste. But at home they needed her, and Lydia was forced to leave school to go back to help her mother look after the family and take care of her elderly grandmother.

Lydia obeyed the wishes of her parents, but she was not very inclined for household chores, and she didn't like cooking. She preferred following her father, not only in the vineyards, but also in the cellar, to the Casale market and in negotiations with the merchants.

Growing up, she became a beautiful woman, autonomous and determined: she dismissed (with a letter!) a very wealthy boyfriend, but in her opinion too dependent on his family, and she was the first woman in the area to get a license. Her car was a "Topolino", Fiat's first car.

As the years passed, she supported her father more and more: in the end it was she who led the negotiations, the only woman in a world of men, without letting anyone intimidate her, without wasting time on talk, and proving a great commercial intuition. In the fifties of the last century, Lydia Arditi was what today we would call a clever manager.

In the cellar, Lydia was very attached to the tradition passed down by her father. Thanks to her, Valpane wine always maintained the characteristics that had distinguished it from the beginning and that made it loved: great structure and a special bouquet of perfumes.

But she was also open to novelties: she equipped the winery with presses and electric pumps, and to the old wooden barrels she also flanked concrete tanks. She even managed to see the arrival of the computer in the company: she found it very convenient that it automatically put supplier names in alphabetical order!

She lived up to 88 years of age, also citing her father's recipe, "Pills from my kitchen and wine from my cellar", as an elixir of long life. And when she saw that her nephew, named Pietro like his grandfather, was taking over the company reins, she realized that once again the Valpane estate was turning page... and that the story continued.

Picture courtesy by Stefano Caffarri

Pietro Arditi

In fact, a new chapter began with Pietro.

Embracing the passion and expertise of his predecessors, he propelled Valpane into the future, while at the same time deeply rooting it in its territory.

Love and respect for nature have always been part of him, ever since he was a boy and said that when he grew up he would be a park ranger. He became the guardian of Valpane and its land, not with a generic environmental awareness, but through his daily work in the vineyards.

"It is the land that makes good wine: the winemaker's job is to respect what the land gives him."

So he chose the path that led him to obtain organic certification in 2017, outside of any trend, as a choice of authenticity.

"My way of working has remained the same, I just have an extra piece of paper."

He also chooses a minimalist approach to winemaking, with spontaneous fermentation without selected yeasts, as a "vignéron indépendant." With him, Valpane enters the core zone of the UNESCO site The Vineyard Landscapes of Piedmont, for the harmony between nature and wine production sites.

His production is rooted in the territory: the grapes he chooses and replants are Barbera del Monferrato Casalese, Grignolino, and Freisa, strictly native vines, which he considers the true voice of his land. But he does not limit himself to Monferrato; on the contrary, with a visionary and forward-looking approach, he chooses to open it up to the world.

He continues to export to Europe, France, and Germany. Great Britain, Portugal, Sweden, and Finland, and smiles at his Barbera del Monferrato Superiore Perlydia served in a bistro in Montmartre. He sends his wines as ambassadors of Monferrato to the USA, and customers send him photos of Barbera Rosso Pietro in the window of Eataly in New York, or his Grignolino Euli in Montana, or Perlydia in Oregon or Hawaii.

He laughs ironically, saying:

"Compared to the more famous areas of Piedmont, we are the non-EU citizens of wine, but our wines are in no way inferior to theirs in terms of character, structure, and longevity."

He sends them to Canada, Japan, and Shanghai. He welcomes as confirmation the recent geological mapping data of the Casale Monferrato area, which finds in his vineyards slightly sandy marl, rich in fine sediments such as silt and clay, similar to those of the Langa di Barolo and Barbaresco. With understatement, he comments,

"lands for red wines, for wines to be aged."

Meanwhile, he found time for his second great passion: photography, which demonstrated his ability to capture the great beauty of the world around him and express his deep love for his loved ones, especially his grandchildren and even his canine friends.

When he died suddenly, it was inevitable to think that he had been called to tend and photograph the vineyards of Heaven.

The surrounding Monferrato region seems to rise up in a wave of emotion and affection for one of its great representatives, but above all for a kind, selfless, generous, and good man. The tribute paid to him is reminiscent of that reserved for his grandfather Giuspìn, almost as if to close a circle.

What remains, to speak of him and for him, are his wines, fragrant and long-lived, lively, vital, brilliant, from several vintages, because, emphasizing the importance of waiting, he used to say:

"I like to give wine time, to allow it to mature through aging that extends over several years in my cellar."

His photographs remain to recount his emotions.

What they said about us:

Here’s a video made by Gianni Messina (in Italian):

Here in a short interview for Grape Collective: